I went downtown to the MLK Library last week, confident that it would be the right place to work on this newsletter. I sat down with the intention of stitching together the best parts of my best drafts from the fragments of work that I’ve done this year and to send something out. You see, I’ve been planning to start this newsletter since January, and my intention was always for it to be a place where I could hold myself accountable to experimenting, playing around, and seeing what I had to say. When I closed shop as a psychotherapist last winter, my goal for the year was always to see where I could recenter creativity as the vessel through which I would explore the work I’d already been doing: work that has been about helping people find psychological freedom and a sense of home inside their bodies, allowing them to be more of themselves…but work that had paradoxically left me feeling burnt out and like I was only doing a tiny sliver of the living—never the less the work!—I feel like I’m meant to do.

While my dreams of this space becoming a connecting, creative outlet grew, I delayed and delayed and delayed the scariest part of this newsletter—the publishing and sharing it with actual people part, people that would actually read it, alone in their homes, potentially judging me and thinking all the worst possible things about my entire worth as a human being (wow, dark). I wrote quite a lot (privately), starting drafts and practicing what I wanted to say in a first issue. However, I never finished anything and definitely never showed anyone what I’d worked on. In the meantime, there were so many starts and stops, so many fragments of writing from moments of this year where some part of me arose and had something to say.

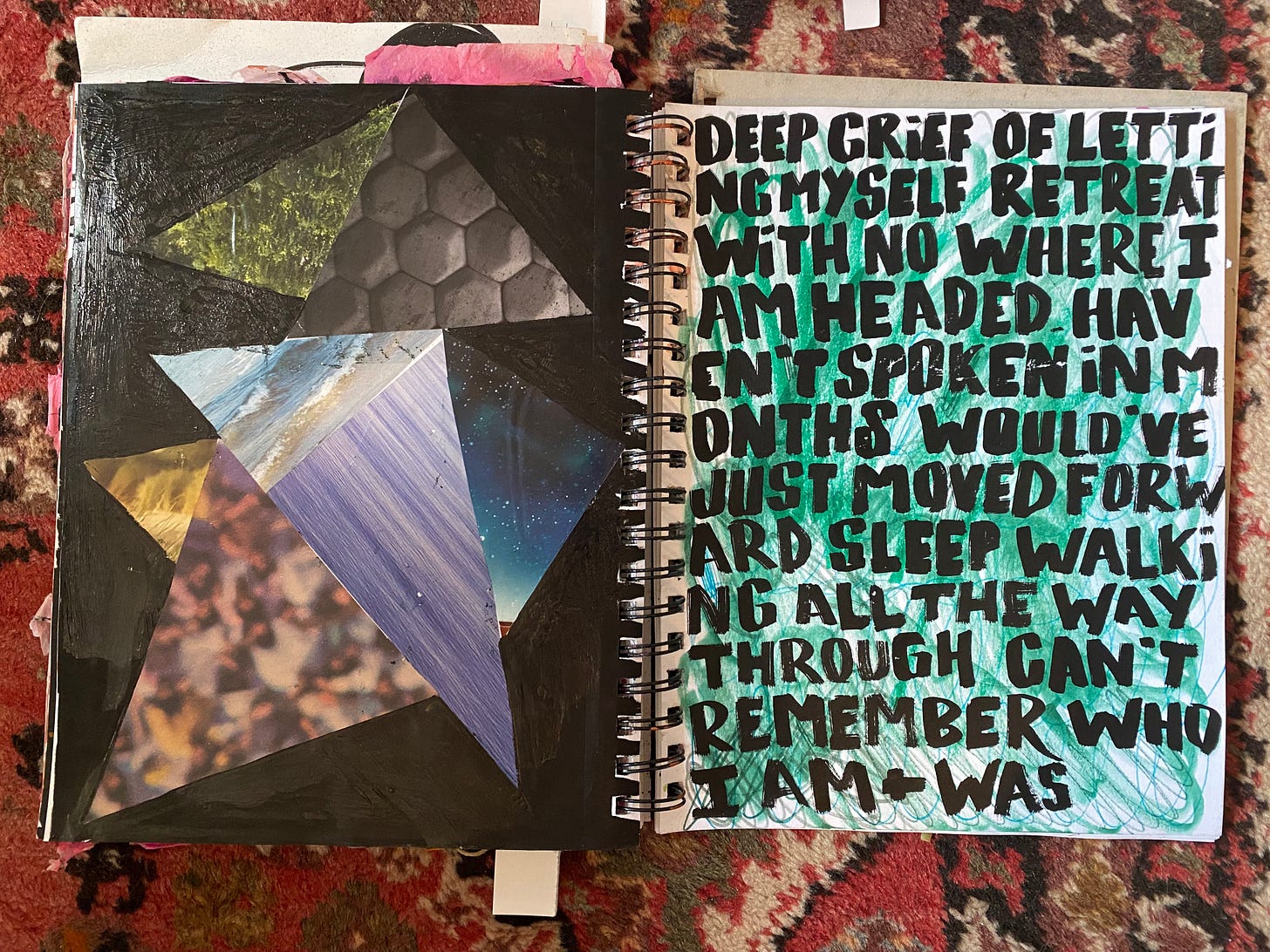

There were drafts full of grief, where I tried to write about a personal crisis that felt so private but so impossible not to write about in some way if I was going to be writing this much. I tried to write about it while obscuring it, watering it down, hiding it in shadows…so much so that I could barely hold onto any one aspect of it with any kind of ownership.

There was a draft about chocolate chip cookies, five different cookie reviews.

There was a piece about one single day in February where, after crying and crying and crying, I got up and sat at my kitchen table with some dried up clay, and rehydrated small pieces of it in a bowl of water. I sat there emotionally drained like a kid after a meltdown, delicately thumbing together a pitcher for cream. I wrote about how that day alone felt like the most nourishing day in years—and really, almost everything I needed from the vast expanse of whatever this sabbatical was meant to be. I wrote about the power of small creative actions as healing.

Some of these drafts have fragments in them that I love (at least, as of today). Some of them maybe I’ll figure out a way to share one day (we’ll see). But last week, as I attempted to mine them for gold …I hated absolutely everything I’d written.

For two hours, I sat at my computer and warred with myself, feeling physically disgusted by the things I’d written (and hadn’t written) and the way I’d written them. I tried to retrace my tracks, writing back into old scenes. But what was once a collection of inspiring jumping off points had become a compost heap[1] and my head was knocking backwards at the perceived stench of it all. In reading my words about my own grief, it all felt stale—like I was hashing out crusted over pain. Writing about leaving my practice felt belabored, and I felt exhausted and bored to still be talking about it. Despite my usual belief that it is in the mundane that we find the scared, suddenly writing about cookies and playing with clay felt grossly trite, and I was sure that it was a waste of anyone’s time.

As I tried to write through my self-disdain, I sounded like a militant art teacher inside my own head: You know better than to get stuck in the details—keep going! This is supposed to be a draft so stop being such a jerk to yourself---you know better. Find a creative solution, you asshole! You’re not listening well enough to the piece itself…pay attention! (Amazing how even trying to have grace for one’s self can become something we judge ourselves for being either “good” or “bad” at.) I tried to not be feeling what I was feeling (surely a foolproof recipe for indeed feeling worse), but I was rolling in self-loathing at this point, wanting to distance myself as much as possible from not just what I’d written earlier in the year—but the person I was during those months and months of so much grief.

Either way, the stories had lost their vitality, and I was trying so hard to resuscitate them.

Dejected and angry, I decided to call it a day, reminding myself that sometimes hours of hating what you’re making is the only way to move toward making something you like…on another day…once you cool the f*ck down.

I made a deal with myself to head across the street to the National Portrait Gallery for at least a couple minutes, so I could attempt to change the channel and fill the well[2].

The new setting was immediately relieving. I felt the self-loathing melt away from me as I got to look at other artists’ work, focusing in on their craft instead of mine. I was drawn into a hallway exhibit that paired pieces by artists that were friends together on the same wall, with captions about how their relationships had influence on each other’s work. I reveled at Frank O’Hara’s snarky poem For Grace, After A Party, in large font on a wall beside one of his friend Grace Hartigan’s paintings. I wondered at the craft of the poem, trying to imagine a sweet but lackluster poem I wrote the day before morphing into something as dynamic as O’Hara’s.

There was a portrait that artist Bumpei Usai made of his fellow artist and friend called Portrait of Yasuo Kuniyoshi in His Studio. I looked at the way he rendered Kuniyoshi’s dress shoe in oil paint, noting the glossy quality of it—an indication of a good bit of medium mixed in with the pigment. I loved the way that some scuffs on the bottom of Kuniyoshi’s shoe were indicated by a kind of scratching away at what was clearly once wet paint—maybe using the tip of a palette knife, or maybe the end of a paintbrush? I dissected his strokes, silently proving only to myself that maybe I could indeed make something as beautiful as that, simply because I felt like I could understand how it was made.

I was feeling revitalized (and necessarily less self-involved), slowly feeling my well of inspiration and connection fill back up. I took photos, I made notes. I got excited for a day in the future where I hope to be in community and conversation with other creatives.

I kept moving through the museum, letting myself fall into the experience.

I turned a corner into a new exhibition and was immediately enamored by a painting by Fritz Scholder: the mix of pastels and earth tones on the beautiful, gritty linen canvas, paint dancing across it with what I imagined to be equal parts ease and fervor. I loved the piece and felt as though I could feel the making of it in my bones. I imagined my body in front of that canvas: brush in hand! arms violently swinging paint into gesture and form! a course of energy rushing through me! total creative flow! I could feel how good it would’ve felt to make something so alive, and I was ravenous for it.

But as quickly as I’d fallen in love with Scholder’s painting, the admiration immediately turned sour, smelling sharply of a jealous rage.

I could’ve made that!

I heard this (unfortunately) familiar sentiment taking up all the space in my skull, overwhelmingly arrogant and angry, resentful for all the reasons I’ve ever felt like I wasn’t allowed my creativity.

If only I had the time/the studio/enough time to practice/if I hadn’t spent the last decade as a therapist…

I caught myself, recognizing the defense of an old, tired story.

Suddenly, I remembered the grueling hours at the library, trying to breathe new life into old pieces, all the parts of me I’d left behind in unfinished poems and essays, waiting for some room to expand into what they were meant to become. I wasn’t just jealous and angry; underneath it all, I could feel my spirit drowning in longing, like a homesickness for a creative part of me that had once been my most intimate ally but I’d left behind over and over again. This was a longing for the person I could’ve become already if only, if only, if only… This rage was actually grief.

Not the kind of grief that filled the stories and fragments I’d been trying to write for months, but a grief for the fact that all those pieces never had anywhere to go: that despite ample time and freed-up psychological resources, despite all the resolve in the world to finally live in alignment with my creative vocation, I still hadn’t finished a damn thing. I still hadn’t released anything out into the world.

While Fritz Scholder’s piece made me alive to my desire to make, it also made me see all the iterations of work he has done to get where he’s gotten, to refine what he has to say through paint. After moving through the jealousy and grief, it helped me to remember to just keep going—that I can’t possibly make anything I love without making a bunch of shitty things first, and doing so relentlessly. Yet the exhibition before—the one where I got to see how friends like O’Hara and Hartigan, Usai and Kuniyoshi riffed off of each other’s work—reminded me of something debatably more crucial: that working in conversation with others (whether you’re an artist or not) not only creates better work, it is often the very thing that makes the work happen at all.

I used to remind my former therapy clients—when they struggled to find the perfect words to express themselves—that sometimes we can only know what we mean to say once we say it out loud, that it’s conversation and relationship itself that helps us refine what we mean to say. Like a rock polishing another rock as they grind against each other, we get to know what we mean to say by saying it, and letting it transform out loud between us and another. There is an alchemy that is created when we’re witnessed that allows us to become more of what we’re meant to be. Once they’re outside of the tiny silo of our own bodies and brains, that alchemy also allows the things we say, make, or do to become more of what they’re meant to be.

So this is why I’m starting a newsletter. I’m sick of grieving all the things that didn’t come to be because I was too overwhelmed in what-if’s, or perfectionism, or even desire, that I missed out on the alchemy that comes from being connected to others in process.

Maybe one day I’ll figure out a way to include all the parts of me that are left fragmented in half-finished pieces. But for now, to all the things I made before and never finished, and all the parts of me that got left behind: I’m sorry I didn’t know how to do with you yet. May what I do next honor you and give you room to know you’re welcome back, anytime.

And to you who’s reading this—may you too embrace the parts of you you’ve left behind so that you can gather them close to you, breathe sweet life into their cracks and crevices, and let them finally be free.

xo,

Carter

[1] Astrologer Chani Nicholas has an incredible app in which she offers recorded meditations and affirmations. In one on creativity, she uses this paradigm of a “compost heap” to describe all the work we make that doesn’t get used. So I thank her for this languaging, which I borrowed for the title of this essay as well.

[2] A concept from Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way, which paints a picture of our creative resourcing being like a well that needs to be refilled by other sources so we can once again draw fresh water from it.

An important post-script…

I don’t exactly know where to put it, but it’s essential to include somewhere in this newsletter today that this piece reflects on the nature of a particular kind of grief, and the scope of this essay is limited. I know so many of us are in a collective moment of grief and horror as we witness the war on Gaza—grief around the horrendous and devastating loss of lives, grief around a deep and painfully complicated story that has lead up to this moment between Israel and Palestinians, grief around rising antisemitism and islamaphobia, grief and rage here in America about being governed by a president who refuses to call for a ceasefire (and all that reflects about the systems of white supremacy through which our country was founded).

Perhaps in another essay I will expand upon this, but I do believe that it is important in the midst of this—not just despite it—for all people in all their different roles to go about the work (creatively, professionally, relationally, whatever…) that is in alignment with their own healing and soul SO THAT we can better participate in the collective’s needs. We cannot be good advocates, listeners, or allies if we are not able to feel or be well. Our capacity to feel into nuances, complexities, grief and joy, is what then steadies us to further educate ourselves, to advocate and fight for others, and to grieve in collective humanity.

As a white therapist and artist, it feels like part of my work to feel into my own emotional experience and to help others do the same (particularly other white folks), so that they can break patterns of dissociation, and awaken to the world outside of themselves, and be present to its pains and needs. And so…I write. Hopefully I will write more essays in the future that better integrate these different kinds of grief and the layers of human experience we all feel at once…because it certainly was not natural to try to separate one from another as I wrote the above essay. That level of dissonance may be something we are all feeling as we go about daily life, in our own particular ways.

May we wrestle with it.

And dear god, may there be a CEASEFIRE NOW.